During severe weather, colored polygons on radar maps represent traditional weather warnings. But for researchers with the Cooperative Institute for Severe and High-Impact Weather Research and Operations (CIWRO), the future of forecasting isn’t tied to a static shape.

Adrian Campbell and Rebecca Steeves, research associates for CIWRO at the University of Oklahoma, were part of a team that recently conducted experiments within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hazardous Weather Testbed (HWT). Their trials experimented with stretching the boundaries of the traditional polygon. The goal of the team’s research, led by the NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL) in collaboration with the Global Systems Lab and Meteorological Development Lab, is to develop methods for forecasters to create dynamic shapes that shift and morph with the hazardous weather threat. The notification strategy would provide continuously refreshed information to allow people to make better decisions to protect themselves. The new approach to warnings is called Threats-in-Motion (TIM).

Campbell says the traditional warning used by the NOAA National Weather Service is incredibly useful but has its limitations.

“Either you’re in a warning box or you’re not. What do you as a member of that public do with that information? If you’re in the box, you’re supposed to take cover. If you’re out of the box, that’s the information you get. There are a few problems with that. You don’t know where the actual pattern is. You don’t know what the storm is doing. You don’t really know what direction it’s headed. You’re just given a binary decision,” said Campbell, who credits other researchers from CIWRO and other NOAA cooperative institutes who have been crucial in developing the TIM framework.

The Hazardous Weather Testbed is a joint project of the National Weather Service (NWS) and NSSL. During the HWT experiments each spring, researchers work side-by-side with forecasters to test and evaluate emerging technologies and science, including forecast models and techniques. Together, they work to test the new products for future NWS adoption and operations.

Campbell and Steeves, alongside other members of the research team, are developing software to enhance the way forecasters issue warnings. For the HWT this spring, they were among those working virtually with forecasters in a controlled simulation to test the effectiveness of both the imaging and communication challenges of the new software.

Steeves said participants were enthusiastic about the potential of the tool, and the valuable feedback the researchers received will allow them to enhance the software further.

“In working with forecasters on the communication aspect of it, we’re learning we can add more customization into the tool for the display, so that’s one of our goals, to let them change how they can create graphics. That’s something we would want to improve upon. We’re incorporating forecaster feedback in as much as we can so we can keep the warning paradigm geared toward what they find useful,” Steeves said.

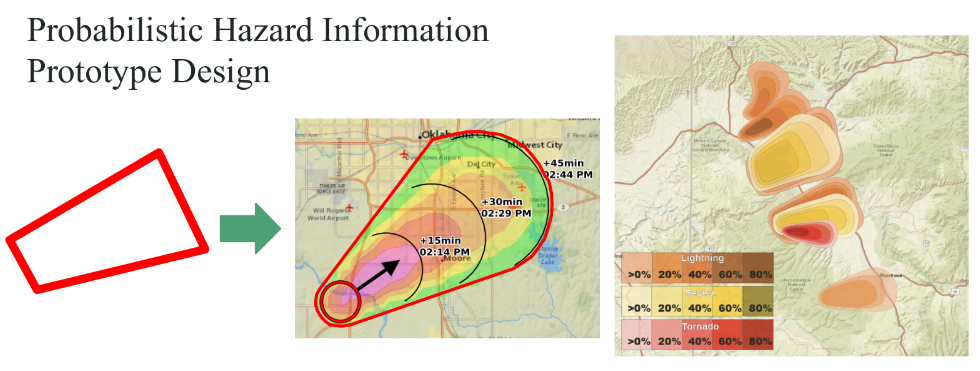

Researchers are also working on ways to allow forecasters to issue hazardous weather alerts that communicate the odds of severe weather impacting an area. In much the same way forecasters can predict a 40% chance of rain, for example, they could predict the probability of a particular storm producing a tornado using percentages – or Probabilistic Hazard Information (PHI). Campbell said those odds can be calculated, but the challenge is how to communicate them clearly.

“We would like to compute this information about the probable path of these hazards like a tornado and throw it up on a map with a cone so that someone can say, ‘I’m at the edge of the cone, and it looks like I have a pretty good chance of being hit.’ Or, they could say, ‘I have a low chance of being hit, but I’m in a mobile home, so my risk threshold is a lot higher. I’m going to take action before a warning is issued.’ Better information allows people to make better decisions,” Campbell said.

Kodi Berry, NOAA NSSL research scientist who led this HWT collaboration, said a major component of this year’s experiments was strategizing how to meld two new emerging technologies.

“We investigated how the PHI interacts with and complements both the traditional and TIM warnings. The possibilities of creating a streamlined new warning system to communicate detailed and meaningful information to the public could be life-saving,” Berry said. “Without the entire team and the vast array of expertise represented, the experiment would have been impossible.”

The research teams are looking forward to returning to in-person HWT experiments next spring. In the meantime, they will analyze recorded data from this year’s experiments to make further improvements for the next phase of weather warning software.

To learn even more about the NOAA Hazardous Weather Testbed, watch the video below, or listen to a podcast here.

Skip to main content

Skip to main content